INTERVIEW 9 Director Shane Acker

SFX: The films started off as an Oscar nominated shot. How did Tim Burton become involved with the feature film versions? Did he see the short and give you a call?

“Ha ha, no. Nothing so exciting. It was more businesslike than that. It was through the creative producer Jim Lemley. When the short came out, and I decided to try to make a feature version of it, I got an agent and he started sending me out to meetings, and I met Jim at one of those. And I wasn’t even there to meet Jim, per se, I was there to meet Bonnie Curtis [producer on many of Spielberg’s films]. But Jim was in the room and he chased me down the hall afterwards and said, ‘I was really struck by your film and I admire your work and I'd love to find something.’ And it happened that Jim had a relationship with someone who knew Tim Burton’s agent. And he’s this kind of independent filmmaker, you know, someone who's willing to take a chance, trying to find unique and interesting properties not really set up at any one place. So it was through that route that I got to pitch the feature version to Tim.”

Was that pitch what we get to see on screen or did it evolve quite a lot in the process of making?

“Oh, it evolved. It constantly evolved. Almost up to the point where in post production we kept evolving. I don’t think we ever had enough time in the story development. We wrote, I think, for five months. We wrote a first draft and then it was very shortly after that that we went right into storyboarding. And then we storyboarded for about seven months and then right after that we went right into production. So we had this really this really accelerated schedule. So it just seemed that we were constantly working on the story for the whole time. Which was really hard, I think. You’re starting to put things together and you’re still trying to figure out the whole.

“But I think in an animated feature that is the modus operandi. The script is sort of the departure point. You really find your film in the storyboarding process. The treatment just kind of opened the door and [Corpse Bride scripter] Pamela Pettler came in and just sort of put some real legs to it, put a real structure in place, and we kinda explored the characters a lot more. And then we took it to the storyboarding stage where it still kept evolving.

“But for me, filmmaking a very much a process. You just keep moving and working and working until basically you run out of time.”

Where did the original idea come from for the short?

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

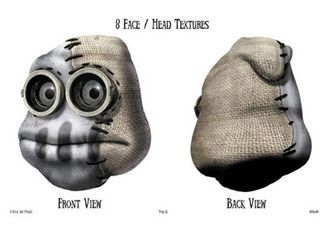

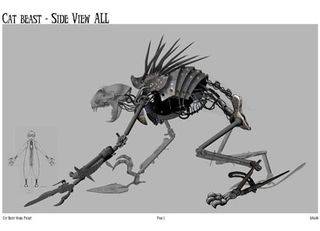

“I wanted to make a post-human tale. I wanted to tell a story after we were gone, and try to imagine what the world would be like. I imagined that there were these little creatures that somehow they had this spark of life. They had this spark of creativity and intelligence. And they were beginning to create a new world, a new culture, out of the remains of our past, out of the things that we left behind. But there was something else. There was something with them of a more animalistic nature, that was trying to pursue them, and trying to take that gift that they had, that gift of creativity and intelligence. So it was hunting them down and taking their souls and it's sewing their skins onto its back, hoping it can assimilate them, become like them. But, of course, it can never can.

“So it’s very different, and the characters are strange, and unique. It’s kinda a man versus nature tale at its core.”

Did you have a target audience in mind, or was this just a film that was going to come out as it comes out, and it would have to find its audience?

“You always think about your audience and I think the audience is primarily somewhere between nine to 15 year old boys. Not that that's the only audience. In some ways it’s very classic this film. It’s like a Ray Harryhausen film, or those old, escapist fantasy films - those B-movie, horror movie things – but with some modern tones and some modern themes. But I just wanted to really try to get at that core, young boy audience. I think a lot of other people today are trying to film for that audience at the moment. I think that’s when I was influenced. I think that’s when I started being influenced by movies, and stated wanting to tell visuals stories, so I’m trying to get back to that.”

The action sequences in the film have a very distinct feel. They’re very “muscular” – less like the action you expect from a Pixar film and more like what you’d expect from a Michael Bay film.

“Ha ha. Thank you. I think. I wasn’t trying to do them in any particular way other than the way I wanted to do them. We wanted to make the film feel a lot more cinematic than a lot of other animated films. We wanted it to feel more dramatic. We wanted the stakes to be real. And then, I just have a penchant for quick cutting. And in animation you’re studying time at one twenty-fourths of a second. I mean, you get so obsessed with time, it's fun to see how quick you can cut things and still get them to read visually. I always have a lot of fun with that. So for me it was just an opportunity to really get in there and have some fun making something rich and dynamic visually, with as much rhythm as a live action film.

“And finding little character moments within the action, so it’s not just, you know, emptying machine guns here and there. The characters are still such a core in the action as well.”

The film was made for a fraction of what a Pixar budget would be, and yet it is visually stunning. What tricks did you use to keep costs down?

“We tried to keep everybody busy all the time, all down the line. So if we were running out of time in one department, like, ‘There’s a backlog of lighting to do!,’ we would just send it back to art and say, ‘Hey, could you guys just paint the lighting?’ Because at the end of the day it’s just a 2D image that you’re watching, even though it’s made in a virtual 3D space. So, we just leaned more heavily on the art guys and had them create lots of the lighting and backgrounds, and using that as projections onto lo-res 3D geometry, which would save on a lot of rendering time, and also saves on a lot of problem solving later on.

“We just kept everybody running all the time. And we didn’t really have a hard-and-fast production pipeline. We kind of just let it evolve to fit the needs of what we were trying to do. So we were a small, lean team. We didn’t have all the kind of the infrastructure and red tape you might have at a lot of other studios. So we were able to work much quicker, I think, and be much more agile in the way that we were approaching the problem solving, which enabled us to get a lot of stuff up on screen.”

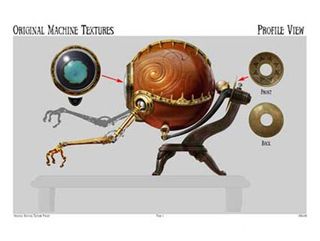

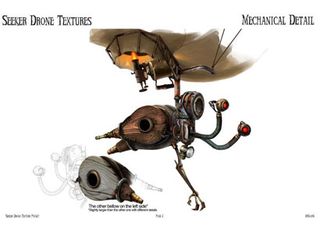

The robots in the movie are particularly impressive. Do you love robots?

“I just love making. I'm a sculptor as well, and a painter, with a background in architecture. So I love the way things come together, and I love working with my hands, and I love details and connections and things like that. So it was a lot of fun to design these things, and the approach we always had for the designers was, we always want it to feel like it could exist in the real world. And to have that tactile nature so that you could believe in it, built from materials that behave as they would in the real world.”

For an animated feature, the film also has a surprising limited colour palette. You expect cartoons to be rainbow-hued, but 9 seems to be a symphony of brown most of the time.

"Yeah it was all these kind of earth tones, and then the two main colours that are used in contrast to one another are red and green. Yeah, because what we wanted to suggest was that even though the world is dead, and there’s nothing living, we wanted to have some life in this world. We found that by using earth tones – this earthy palette – especially on the characters, it puts some nature into the mix. And we also wanted the characters and the world to sit together, so that you feel that the characters came out of this world. So we found that by keeping that palette kind of constrained you got that sense, and then using real sharp contrasts of red and green brought some intensity to some of the more dramatic or intense moments in the film.”

This was your first film as director. What’s the biggest thing the experience has taught you?

“Oh boy. I think that one of the things that we all learnt on this is that we might have rushed into the making sooner than we should have. We should have spent more time in story development, written a couple more drafts of the script perhaps, and spent twice the amount of time we did on the story. Not that you can ever say, ‘We’ll take a year and have an air tight story,’ because you’re always going to evolve it. But I think you need a little bit more a firmer ground before you start doing the production. Because once you start doing things one way, it’s harder the change direction, and you’ve already spent that money, so you have to take that footage and fit it into whatever reworking of the story you’ve come up with.”

SFX Magazine is the world's number one sci-fi, fantasy, and horror magazine published by Future PLC. Established in 1995, SFX Magazine prides itself on writing for its fans, welcoming geeks, collectors, and aficionados into its readership for over 25 years. Covering films, TV shows, books, comics, games, merch, and more, SFX Magazine is published every month. If you love it, chances are we do too and you'll find it in SFX.

Most Popular