Why Dark Souls 3's colour-coded multiplayer system is the best yet

There are many mysteries about Dark Souls 3’s multiplayer, but the way it’s presented is as clear as you get. Anyone who played cops and robbers as a child sees scarlet red invaders being set against blue sentinels, and knows in their gut who to root for. But red vs blue is only the starting point for Lothric.

A big part of DS3’s multiplayer is how it is woven into the ‘main’ game. Souls multiplayer has always revolved around the idea of a host being able to summon players for co-op, and by doing so opening themselves up for invasion. You don’t enter matchmaking, but as soon as you choose to act as a host, summon or invader the game begins brilliantly mixing up players who want to help with players who want to hunt.

The original Dark Souls’ online issues could make PvE and PvP a lonely experience. But DS3 is buzzing, every location packed with summons, invaders and several other flavours of player, all waiting to get a piece of the action. On top of this there are all sorts of permutations to do with the covenant system, most of which have a mechanical and a lore purpose – join Aldrich’s Faithful, for example, and you guard a single area of the game. You are then passively summoned into that area, a blue phantom with a red tint, alongside other Aldrich Faithful, and gang-up on those trying to take down that Lord of Cinder. These players choose to play on home turf, with the chance of a numbers advantage, in exchange for a firm boundary.

This is just the surface of the covenant system, but what makes everything work in DS3 is that every player is realised in a way that makes sense. Designers tend to focus on character silhouettes, but in a game like this, where a player could be wearing anything from a halo to a toothy treasure chest on their head, bright colour-coding is preferred as a way to bring order to the chaos.

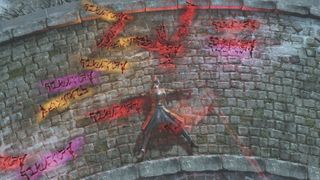

You are bright red. The host is seen as normal. Beside them are two shining white phantoms. A third, resplendent in the golden yellow of a Warrior of Sunlight, rises from the ground. Another scarlet invader appears, joined by a ‘mad’ purple phantom. A royal blue Darkmoon arrives to protect the host. In the battle to come, with no voice or text communications required, everyone instantly knows which side they’re on.

The fact the host is so drab is another genius touch. The host is always the target – kill the host and it’s match over – and so the action has something to keep it anchored. Whites and yellows and blues want to kill reds and oranges and purples, but the invaders need only take down the VIP.

That in itself is a clue to how DS3 works – it doesn’t have modes but incorporates their rhythms anyway, slipping and sliding from deathmatch to king of the hill to VIP to Benny Hill chases. As an invader you can start in a duel, mano-a-mano. A minute later you’re in a 2 vs 1, before a blue gets summoned in to make it 3 vs 1 and, just as all hope is lost, another red arrives to make it 3 vs 2. Things can get even more hectic but, amidst the storm, that single rule remains the only important one: kill the host and you win.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The colour-coding of online players isn’t new to DS3, but it allows this entry to push multiplayer further than Souls has ever managed before. The big difference is numbers: seeing four or five players at once in Dark Souls was almost unheard-of, whereas here these kind of huge brawls are common. On top of this is the environment, where enemies will still attack the host and phantoms, traps will trigger, and there are all sorts of blind alleys and ambush spots.

It works because everything remains clear. Forget the covenant lore, the incredibly-detailed environments, and the mob of enemies gatecrashing from one side. The whites shine, the reds blaze and the blues glow among them, letting you keep your head while all around are losing theirs. A key PvP tactic is parrying, and now the little coloured flashes let me do it by instinct.

One covenant is even dedicated to a kind of trickster role, the Mound Makers, which enter the host’s world as purple ‘mad phantoms.’ They can either be summoned or invade – but regardless they can always go for everyone else. They can help gang up on the host, protect him, or suddenly change mid-fight from a wingman to your assassin. Again the visual communication is instant.

One quirk that has to be mentioned is FromSoftware’s mischievous side, which always gives players the tools to misdirect. In DS3 there are a couple of rings that allow hosts to appear with the white glow of a summoned phantom, and vice-versa. The disguise is not foolproof, because an alert invader will remember the host’s name from their arrival (which never changes), but it’s a way of countering those who trust blindly in the colours, and snatching victory via ruse.

In a way this speaks to Dark Souls’ foundational principles. The way phantoms are coloured is loosely tied into the lore, but the real reason for it is how striking it looks and, from this, the sheer usefulness of the information to a player. It’s a purely game-y touch in this Serious Fantasy World, but so beautiful and practical it has become an indelible part of the Souls identity.

It encapsulates the roleplaying that runs through these games, but is so interwoven with moment-to-moment decisions you barely notice it. Who cares about the specifics of the lore? Our actions cast us as a crimson villain, a shining paladin, a noble blue defender of the weak, and so much more. When things kick off each of us knows where our heart truly lies, and plays the part full-blooded. No wonder the epic brawls of DS3’s PvP are one of the greatest shows on Earth.

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.

Richard is an experienced games journalist with over 15 years of experience. Currently the News Editor at PC Gamer, he has also written for Edge Magazine, Ars Technica, Eurogamer, GamesRadar+, Gamespot, the Guardian, IGN, the New Statesman, Polygon, and Vice. He was also the editor of Kotaku UK once upon a time. He also wrote the Brief History of Video Games, a full history of the medium.

Diablo 4 dev is sending 666 buckets of literal bugs to "meat their maker" at a charity for hungry birds

The cult vampire third-person shooter that nearly bankrupted the small studio that made it is getting a film adaptation from the Transformers producer

Fallout mod site says it's like players are downloading Skyrim "twice every second" after Amazon TV series drives fans back to the open-world RPGs

Most Popular