So far, Super Mario Maker for Nintendo 3DS (henceforth SMM 3DS for brevity’s sake) seems to have been defined less by the features it has than the ones it’s missing. Yes, you’re limited to sharing levels locally rather than online. Yes, the Mystery Mushroom that allowed Mario to transform into a range of different characters - many via the use of amiibo - is no more. And yes, both of those omissions are disappointing. But their exclusion points to a decisive shift in approach, and the finished game makes Nintendo’s aims for this portable version all the more plain. If Super Mario Maker was about giving everyone the ability to make their own Mario levels, the 3DS version is a creative toolkit for Mario connoisseurs. It doesn’t just want you to make Mario levels. It wants you to make really good ones.

In order to achieve that, Nintendo has realised most players will need a little more guidance than last time. To which end, it’s promoted Yamamura (a pigeon with Mario’s ‘M’ on its chest) and Mashiko (a friendly woman who looks like a call-centre operator) from the e-manual to host an in-game tutorial. This is arranged into a series of lessons, with each subsequently split into basic and advanced techniques.

You can still just plough ahead with your own level experiments if you prefer, but it’s worth setting aside some time to sit through these lessons. As you’d expect, they’re charmingly presented - Yamamura’s advice is a series of coos translated in parentheses – but more importantly, this series of design best practices encourages you to think more deeply about course creation.

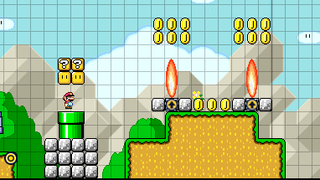

Your unlikely tutors patiently and thoroughly talk you through everything from course structure to power-ups and enemy behaviour. Typically, you’ll be given a template to place objects within a small section of a stage, which you’re then asked to play through. Then you’ll complete a short pre-designed course, after which Yamamura will explain some of the details. With coins, for example, he’ll talk about placing them to make players jump, setting a trail to lead them somewhere, or to highlight something of importance.

One early lesson even includes a tricky section in a low-ceilinged cave that requires you to jump exactly three grid squares high to progress. You’ll probably wonder what’s going on until Yamamura uses it to demonstrate how you might improve a course with minor changes, like widening the opening to make the jump more manageable. Making a course navigable is the first step, making it fun is the next, and making it surprising is the third, handily illustrated by a Question Block producing a giant Goomba.

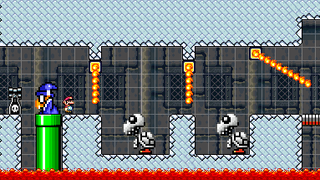

Yet there’s only so much you can learn from following instructions. True appreciation – and potential inspiration – comes from the practical lessons provided by the new Super Mario Challenge, a series of 100 levels that replaces the Wii U game’s 10 Mario Challenge. There are 18 worlds here, the completion of which yields new pieces to use in building your own stages. That’s a questionable change from the daily drip feed of its home console predecessor, since less capable players will struggle to access some key course elements as the difficulty steadily escalates. Failing a stage five times lets you choose whether to receive an item to help you progress, but that’s unlikely to be much comfort to anyone who’d rather not have to jump through hoops to build the course of their dreams.

Unlockable medals further underline Nintendo’s choice to target more committed player-creators. These accomplishments are sometimes a course’s raison d’etre: it might be simple to finish conventionally, but the medals will incentivise skilful play or meticulous exploration. World 1-1, for example, invites you to reach the goal pole as Fire Mario, which is straightforward enough. But the subsequent challenge that unlocks – to finish with 287 seconds left on the clock – is anything but; even with the use of a warp pipe, it’s a tight squeeze. Challenges that sound easy on paper rarely turn out that way. One asks you to reach the goal while carrying a P-switch: triggering it makes for much smoother progress, while keeping hold of it requires precision jumps across narrow platforms. Another demands you finish without ever pressing left on the d-pad, encouraging you to take greater care over the timing of every leap.

This isn’t merely a case of adding longevity through replay value, it’s also a way of enriching your Mario education. Each course functions as an entertaining test in its own right, while simultaneously demonstrating ways to offer a tiered challenge to those who play your courses. It’s a pity SMM 3DS won’t let you add your own medal requirements; you can subtly encourage players to test new approaches, but they’ll gain no tangible reward for doing so. But it’s another step in learning to be a genuinely super Mario maker. The presence of Yamamura and Mashiko here – who’ll advise you on what to expect before each world as well as giving you your course items at the end – is another reminder that you’re not just playing for pure enjoyment. You’re here to learn.

As well as those 100 Nintendo-built stages, you’ll be able to access select levels created within the Wii U game (note the emphasis on ‘select’: obviously anything using a Mystery Mushroom is out). Unfortunately, this currently requires an update which isn’t yet available to press, so at the moment it’s unclear exactly how well – or otherwise - that works. You won’t, however, be able to award stars or add comments to encourage other creators: another nagging reminder of what’s been lost in the transition to a portable format.

Still, it would be unfair to focus on what isn’t there given the quality of everything that is – even if much of that is down to the brilliance of the original’s interface which has been preserved here. SMM 3DS is much more than the quick-and-dirty port many assumed it to be – heck, 100 new Mario courses will be more than enough for some Nintendoites to double-dip - and its shift towards a more carefully curated approach to creation makes it a worthy investment for anyone prepared to admit they still have a lot to learn about building a better Mario level.