Myth in games

The timeless origins of 10 gaming tropes

Better Villainy Through Palette-Swapping

While “Shadow” denotes any big jerk who lurks near the end of a quest, here’s another example of games’ literality: the Shadow in many games is a mirror image of the hero. For the character, this represents confronting their own darkness; for developers, it’s a quick way to make the player feel useless without having to design a new baddie!

Hallmarks:

- Flaming hair, dark clothing, glowing eyes: whatever will “evil up” the main character model in the space of a Friday afternoon.

- Knows all your moves, but faster. Has all your gear, but better. Remember in Twins, how Danny DeVito was like Arnie without the good bits? You’re Danny DeVito.

- If anyone in the game is to be made of liquid metal, it MUST be this character.

Above: World Heroes’ final boss, Geegus: a liquid-metal version of every character in the game. What a gyp!

Some Examples:

Shadow Mario (Super Mario Sunshine), Star Wolf (Lylat Wars), anyone whose name begins with the adjective “Dark.”

Above: The least scary thing you’ve ever seen

Where’s This Come From, Then?

This idea refers to the German myth of the Doppelganger: an identical being to oneself that may be helpful or deadly. Carl Jung advanced the notion that the “Shadow Self” represented the deepest truths of one’s own mind, which, if confronted, could open the door to profound self-revelations. Or at least a new area.

How Do Games Do It?

In the Mega Man games, the evil robots serve as partial Shadows, guarding new abilities until the hero can prove himself worthy. Miyamoto characters often have a memorable Shadow, the best example being sneering, greedy Wario: Sonic had a similar relationship with Knuckles, until the two paired to launch a thousand icky fanfics.

The Warrior

Truth, Justice, All That Good Stuff

Videogames have always loved a good, honest brawler. There’s something more to the Warrior though: while defined by their prowess in combat, they manage a Zen-like awareness of their part in the drama. The Warrior is the one who’s been in it long enough to know the rules and learned to play their role: that of a scowling, well-armed badass.

Above: Some Warriors take it too far

Hallmarks:

- Talks like if Tom Waits had just drunk a bottle of turpentine.

- Dresses like ‘80s action movies never went away; strangely, has never been told that tank-tops and stubble look a bit butch.

Above: A whole mess of testosterone

- Much like Dr Dre, was strapped with gats when you were cuddling a Cabbage Patch.

Some Examples:

Regal (Tales of Symphonia), Marcus Fenix, Sheik (Ocarina of Time), innumerable muscular headband-wearers throughout gaming history.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Above: Possibly even this one

Where’s This Come From, Then?

King Arthur, St. George and Siegfried blur the line between fighter and holy man: always ready for a scrap in the name of good. With the Crusades, the notion of the Warrior was used to enlist soldiers to fight for what was believed to be the soul of civilisation; in our time, figures like Churchill and Washington have been similarly canonised.

How Do Games Do It?

Just like anyone who grew up with ‘80s characters like Rambo, Robocop and Oliver North, videogames have always admired a tough, plain-spoken ass-kicker of a hero. Such a figure is Solid Snake, whose entire story arc is one big exploration of what it means to be a soldier; or Ghouls ‘n’ Ghosts’ Sir Arthur, whose entire storyline is one big exploration of what it means to be a soldier with natty boxer shorts.

The Boon

God’s Freakin’ Gift to Humanity

This is what the entire quest has been moving toward. It may be a sacred weapon, or the elixir of life, or freedom from tyranny; whatever form the Boon takes, a good story will leave audiences with the feeling that it was all worth it for this. Until the sequel, anyway.

Hallmarks:

- You’re okay making a cuppa while this cutscene plays. It’ll be still be going when you get back.

- If a game’s going to surprise you with a dodgy “theme song,” here’s where it’ll do it.

- Thank you, but the Boon may be in another castle.

Some Examples:

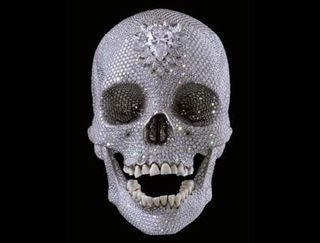

Defeating the Chimera (Resistance: Fall of Man), escape from Hell (Doom), Damien Hirst’s “For the Love of God” (50 Cent: Blood on the Sand).

Above: Whatever gets you out of bed in the morning, homes

Where’s This Come From, Then?

As the Mentor shows the hero who to be and the Shadow dramatises what elements must be overcome, the Boon shows what the quest is about. Whether it’s Hercules’ victory over the powers of death, or Hamlet’s unmasking of his father’s murderer, the Boon is what shapes a quest and tells audiences what to hope for.

Above: Hope, but don’t dream the impossible

How Do Games Do It?

Stories from Donkey Kong to Resident Evil 4 have the player striving to rescue a princess, but games have – due to their target audience as much as anything else – worn this one into the ground. Just as old-school games had players fight for nothing more than a new high score, many modern games’ final offering to the hero is less important than that offered to the player: Achievements and unlockables take it back to the days of high-score contests, when the Boon wasn’t a plot point so much as a feat of gaming prowess.

Sep 17, 2009

What do developers love? Falling back on these new-school cliches

Copy, paste, unoriginality! The most overused archetypes of all time

VIDEO: Gape in awe at these monstrous turd-cutters!

Oh, that's why the Stellar Blade devs were terrified by demo players: one fan's spent "about 60 hours" maxing Eve's skill tree before the action RPG is even out

A new Taylor Swift song mentions GTA, but some remember it mentioning Baldur's Gate 3, Final Fantasy 14, and more in hilarious Twitter trend

Most Popular