By Edward Gross

While Indy fans may not hold the spin-off TV series, Young Indiana Jones, in the same regard they hold the big-screen version of the character, it’s nonetheless a project that is dear to George Lucas’ heart, as will be evident to anyone checking out Paramount’s first collection of episodes released on DVD in America this week. Most notably, check out the in depth historical documentaries that accompany the episodes themselves to fully grasp his original inspiration for the show.

Back in 1992, Lucas had become intensely interested in education and was developing interactive technology that would make it more interesting for young students to learn history and geography. Lucas came up with an idea for an educational CD-ROM he called A Walk Through Early Twentieth Century History with Indiana Jones, but he liked it so much that he decided to turn it into a television series, writing the story for the pilot episode himself.

The result, which aired on ABC from 1992 to 1994, was not your typical episodic fare. The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles was perhaps the most ambitious television show ever launched: It was a series of short motion pictures rather than conventional hour-long episodes, and it attracted big-league Hollywood writers and directors, such as Jonathan Hensleigh, Nicolas Roeg, Frank Darabont and Simon Wincer. At the center of it all was Lucas, whose enthusiasm for the series was palpable.

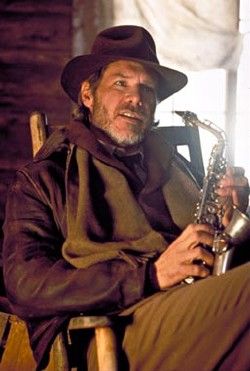

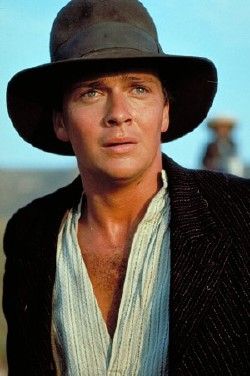

Through the course of the series, audiences would meet Indiana Jones at a number of different ages, most notably as a small child (as portrayed by Corey Carrier), a late teen (Sean Patrick Flanery, Greg Stillson of the TV series based on Stephen King’s The Dead Zone) and an elderly man (George Hall). As a favor to Lucas, Harrison Ford reprised the role in a framing sequence for one episode.

Frank Darabont, who wrote and directed The Shawshank Redemption and the forthcoming adaptation of Stephen King’s The Mist, believes Lucas’ passion for the project grew out of a new-found liberty. He postulates that the mini-mogul felt that Lucasfilm and its many limbs reached a level of prosperity – both creatively and financially – that would allow him to step back from CEO duties and concentrate on being a filmmaker again.

“I think he was coming out of 10 years worth of, ‘Okay, I’ve got to build this empire and make sense of it. I’ve got to make this machinery run.’ Without such guidance, companies like Lucasfilm tend to erode after a while, and it needed a steady hand on the tiller. I think he was now putting on his filmmaker hat again after quite a while, and this was his means of getting his feet wet. This has been my understanding from talking to George and others [at Skywalker Ranch] during the creative process. Young Indy was George really hopping up on the horse, picking up the shield and sword, and saying, ‘We’re filmmakers again! We’ve been businessmen for too long.’ This was his way of coming out of that period and sort of paving the way, I think, for the next Star Wars trilogy.”

Lucas pointed out that some of the CG innovations developed during Young Indy, which allowed for first-rate visual effects on a television budget, helped him to decide to take on the Star Wars prequels. The point of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, however, was not spectacle and action, but one character’s trek toward personal discovery amid the sweep of great events. The show was shot on locations around the globe, with a rather introspective Indy ranging in age from eight to 20. The gist of the series was that in the course of his adventures and travels, Indiana Jones would bump into historical figures throughout the early years of the 20th century.

Before the series’ debut in 1992, Lucas told The New York Times, “If this wasn’t called Indiana Jones, it wouldn’t have been made. I told the network this is not going to be like the movies, that this is not an action-adventure film, but it’s a coming-of-age film. It deals with issues and ideas. It’s not a high-tech adventure thing. So far everything has gone well, but when the scripts came in, they got a little nervous. It was the other shoe dropping. It’s like, ‘Where’s all the action? Where’s all the jeopardy? Where are the bad guys?’ Well, we’re basically doing Tom Sawyer here. It may not be as exciting as the Indiana Jones we think of, but it’s much more emotionally powerful. It’s a very, very high-risk project. Television is the one place where you can do 20, 30 or 40 hours of programming and tell a big story.”

Some critics were opposed to the premise, deriding Indiana’s encounters with real-life luminaries such as Picasso and Freud as a bastardization of history. Lucas didn’t agree. “I’m not oversimplifying,” he said. “I’m not telling you the story of Teddy Roosevelt in 15 minutes. All I’m doing is introducing him to you. All I’m saying is that this man is Teddy Roosevelt. The idea is for the viewer to say, ‘I’m interested in that character. I want to learn more about him.’ The show is designed to spark the imagination and curiosity of students and acquaint them on the barest level with these figures.”

Adds Jonathan Hensleigh, “What George wanted to do was take history exactly as it happened – not to fudge history at all – and then we just kind of stick Indiana Jones in the middle of it. The best example in the feature films is in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade when Harrison Ford, playing the older Indiana Jones, accidentally gets an autograph from Hitler. I think that’s the only time in the features where Indiana Jones comes across a real historical figure. Well, on the series we would do that every single week.”

Indiana Jones managed to repeatedly thwart the Nazis and recover both the lost Ark of the Covenant and the Holy Grail, but he got his ass kicked by Jerry Seinfeld. Shows like Seinfeld, Roseanne and Murder, She Wrote dominated the upper echelons of the Nielsen ratings in the early ‘90s, but Young Indiana Jones began in the middle of the pack and gradually slid downward. Though Lucas offered a well-written, good-looking show every week, the audience failed to stick with the series and ABC was forced to pull the plug. Overseas, the show fared much better, but in spite of the difficulty in finding an audience for it, the creative team remains impassioned boosters.

“First of all,” says Hensleigh, “I never wanted to write network television. But this allowed me to write network television that wasn’t in the usual format. In other words, I didn’t have to do some stupid cop show or sitcom. This allowed me to essentially do what were one-hour feature films shot by feature directors about historical subjects with wonderful production values. I also believe I learned more about the entire process of filmmaking – going from the script through the preproduction meetings, the meetings with the director, the actual shoot, the editorial process, the scoring with music – from this show than any other experience I’d had. What was truly extraordinary about this is that I emerged from this show having made the equivalent of several feature films that appeared on screen exactly as I’d written them. That was just invaluable.”

Darabont agrees, noting that he was given the opportunity to write the kind of script that the typical Hollywood executive can’t even fathom. “One of the episodes,” says Darabont, who points out that Lucas and the entire writing staff worked on each script together, “was an insightful little story about a boy meeting an old man as they’re both running away from home. The old man happens to be Tolstoy at age 80. Well, I’m just not asked to do that kind of thing. Usually when Hollywood asks me to do something, it’s more like, ‘How do we blow this thing up in a bigger and better way than we did last time? What is the clever quip after you empty the Uzi’s clip?’ After I met with George, I thought, ‘Wow, this might be a way for me to grow personally as a writer, because I want to write more character-based things.’ It’s not that I don’t like action or horror movies, but as a steady diet? My teeth were rotting out from it. I needed to start eating some kind of substantial soul food, if you will, and I was able to go off and do that with George. I’m eternally grateful to him for giving me that opportunity. When I finally got around to writing Shawshank Redemption, I know I was drawing on the courage I had found as a writer working on Young Indiana Jones – working on purely character-driven films, which is what Shawshank is.”

Young Indiana Jones, Darabont believes, was more than an ambitious and unique television series. It was a rekindling of George Lucas’ creative muse. “There was such a positive creative energy from him, and it’s the only time in my life I’ve experienced something like that,” he says. “That’s why I glow whenever I talk about this series. What it brought to me personally was so much creative juice and satisfaction. It’s one of those things I will look back on for the rest of my life and say, ‘Wow, that was truly a one-of-a-kind experience.’”

The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones - Volume One is available on DVD in the US from today, Tuesday 23 October. The second volume will become available in December.