Jordan Thomas has been in the games industry since 1998, and has worked on some of its most famous games. He created the infamous Shalebridge Cradle level in Thief: Deadly Shadows, co-developed Bioshock's Fort Frolic with Stephen Alexander, and was Creative Director on Bioshock 2. After parting ways with Irrational post-Bioshock Infinite, Jordan and Stephen founded their own games company named Question and recently released The Magic Circle, a satirical send-up of the game development process.

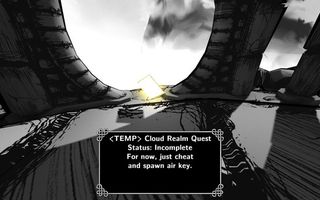

Having spent years working on games with dark themes and serious tones, The Magic Circle marks the pair's first attempt at a comedy. It casts the player as a tester of a high-fantasy game languishing in development hell, largely due to the perfectionist attitude of its arrogant auteur, Ish Gilder. Lampooning everything from cut-scenes to crowdfunding, it's influenced by what Thomas has both seen and done during his years as a mainstream developer.

"The thing that struck me over and over was the sort of religious language that both creators and players would use about what games 'Should be’ - with a capital S - and the almost crusades that they would lead against one another in pursuit of some principle of play," Jordan explains. "I couldn't help but be inwardly laughing a little at the lack of self-awareness it takes to elevate this artificial world to almost more important than ours."

In the Magic Circle, this kind of blind sincerity is explored through warping and inverting various familiar aspects of mainstream game design. The starting point for this was the game's characters, who the team created to represent the various personalities who influence game development. Ish Gilder, for example, is an embodiment of the auteur developer, whereas his subordinate Coda encapsulates the most extreme examples of a game's fanbase, those who internalise a game's mechanics or message to the point where they believe they understand it better than the creators themselves.

"I think extremity is a good point of origin for humour, right? And so, the characters were crystallised and heavily exaggerated caricatures. In a lot of ways, if I'm honest, of positions I've heard people take in the industry, myself very much included," Jordan says.

But Jordan didn't want The Magic Circle to be a vindictive, insider’s teardown of the games industry. He wanted the player to be directly involved in the humour, and in the process engineer an alternative to the viewpoints espoused by the game's characters. During the 'testing' of The Magic Circle, the player encounters the Old Pro, an AI character from an earlier version of the game who has become sentient and wants to escape the half-finished world.

To this end, he gives the player the ability to re-write pieces of the game's code, including the ability to alter the AI behaviours of enemies. So for example, you can take the railgun of a mech and program it onto the head of a dog, or give a corpse the ability to fly. "What we didn't want was to use the structures of another medium, which are mainly just dialogue and art, to say 'Look how stupid games are, you guys, am I right?,'" Jordan notes. "That would have seemed almost unethical, a cheap-shot, and so we wanted to essentially hand you some systems to allow you to tell systemic jokes." Rather that simply scripting humour, Thomas wanted gaming to be both the butt and the means of the joke. Games’ systemic interactivity makes them a unique narrative delivery and creation tool, but rarely has comedy been the goal so far.

Through its blend of scripted jokes, FPS-esque level design, and AI-manipulation, The Magic Circle uses old-school methods to mock old-school design philosophies. But it also hints at something new, concluding with the notion that "gaming needs new blood". For our purposes this is a fitting end, as the alternative The Magic Circle nudges toward - the idea of creating collaborative humour through systems - is being explored wholesale by another developer in a way that couldn't be more different from Question's approach.

Boneloaf's Gang Beasts is a multiplayer fighting game where players take control of what are essentially drunken jelly-babies who punch, kick and throw each other around various arenas. The core team comprises of three brothers; James, Jon, and Michael Brown, and their close friend Matt Thomas. Fresh out of University, Gang Beasts is their first game, and prior to the formation of Boneloaf, only Michael had any programming experience. When I ask them for their names and job titles at the start of our interview, they begin sniggering between one another before James finally states "We don't really have job titles."

Gang Beasts started life, oddly enough, as a comedic high fantasy game called Grim Beasts, before the team decided it was too complicated for their first game. "We tried to simplify it by making a Space Opera," says James, "But that proved even more complex."

Eventually, Boneloaf took the physics-based characters they'd used for Grim Beasts ("we didn't have an animator", notes James), created a simple punch mechanic ("They were more slapping than punching, but it was still somewhat satisfying") and made it multiplayer ("We're brothers and wanted to fight each other"). They took the prototype to a local game dev meet-up, and after someone posted footage of the game online, Gang Beasts' popularity skyrocketed.

What makes Gang Beasts interesting is that all of the humour emerges from player interaction. It sets the stage and hands you the actors, but everything else is down to whoever has a controller in-hand. This poses some intriguing development problems. Because the game is so player-driven, everything that Boneloaf does to fashion the humour in the game has to be done indirectly.

One approach is to make sure each arena is diverse and creates new obstacles and opportunities for fights. "Very early on we just looked at, what's the smallest level we could possibly conceive, what's the most ridiculous level, what's the largest area we can work with? Can we work with heights?" In addition, Boneloaf is embracing the concept of escalation. For example, a level that sees you fighting on top of a pair of speeding lorries will pass you beneath an increasing number of painfully sturdy road signs. "Ultimately what will happen is there will be a driver in the truck, hopefully, and procedurally they'll start to veer towards hazards the longer you're playing," James says.

The nature of how the characters fight is equally important. "The biggest thing for us is not to make them look like they're capable or trained fighters." Alongside drunken punches and grappling, the team is planning to add moves like standing headbutts and doggy-paddling, and have already included dropkicks. "They're kind of Eric Cantona dropkicks," James emphasises.

But there's also an element of restraint involved. At the community's request, the team did a test for adding blood in the game. "But we didn't limit the amount of blood that could spawn, and we made it slippy," adds Michael. "The game was dropping frames because of it, and it literally is one of the most traumatic experiences I've had."

In a way Gang Beasts seems like the natural endpoint of what the Magic Circle advocates. And yet, the fact that Boneloaf feel the need to add some more direct structuring elements, a - little bit of story, a touch of tournament mode - suggests that it’s less a different approach and more a different part of the same cycle. Both projects’ comedy relies on a balance between structure and chaos, and it's simply how and where they find that balance that makes them seem so different. The Magic Circle uses script and actors to set up a world falling apart, and then introduces a few systems to let the player rip apart what's left. Gang Beasts ostensibly lets its players run wild, but only within the confines of each carefully constructed arena, using the painstakingly designed move-set to become champion of its "midnight brawl in a pub car-park" style of wrestling.

In the end, it seems making a successful comedy game is largely about how you deal with the player, regardless of whether your game relies on a smart script or physics-powered slapstick as its focal point. It's about how developers anticipate the player's actions months, even years before they ever lay hands on the game, and set up their game to react accordingly. Truly interactive humour for a truly interactive medium. "The real joke of working on any game,” Jordan concludes, "is the player has written their own punchline long before they get there”